Great Mid-Century Designers 101: Florence Knoll

When describing her work, Florence Knoll has said that she did not merely decorate space—she created it. Her design legacy proves the truth of that statement. She did far more than just place furniture in a room. She meticulously planned each space to maximize efficiency and ensure it met the needs of the people using it. Where gaps in functionality existed, she designed furniture to fill them. As an architect, interior designer, furniture designer, and business owner, she made history and has been credited for “develop[ing] the idea of the modern office and pioneer[ing] the interior design profession.” (Knoll)

Florence Knoll: Functional, Organized, and Never Flamboyant

Florence Knoll (née Schust) was born in 1917 in Saginaw, Michigan. Although orphaned at the age of twelve, she would go on to have “perhaps the most thorough design education of any of her peers.” (1stdibs) Her guardian sent her to the Kingswood School for Girls in suburban Detroit. Kingswood was part of the Cranbook Educational Community, which also included the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Knoll had shown an early interest in architecture and design and soon got the attention of Eliel Saarinen, the head of the Academy. While a student there, she became close to the Saarinen family and, particularly, Eliel’s son Eero, the now famous architect and designer. In her time at Cranbrook, Knoll also befriended future design legends Harry Bertoia and Charles and Ray Eames.

With a recommendation from the elder Saarinen, Knoll went onto study under three “Bauhaus masters”: architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer in Boston, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology. (Mies van der Rohe is known locally for designing the TD Centre at King and Bay in Toronto.) Knoll was eventually hired by Mies van der Rohe in 1940 and was his sole female employee. As the only woman in the firm, she was often assigned project interiors, the work “her male colleagues were consistently neglecting.” It turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Knoll would not only excel at this work, but also set a new standard for corporate interior design.

Although she faced resistance from corporate clients wedded to the status quo—“heavy, ornate desks placed on an angle” and “closed-off and claustrophobic spaces”—she followed the tenets of her Bauhaus mentors, focusing on creating functional, efficient spaces. In 1941 she met Hans Knoll, a man who shared her dedication to modernism and was just launching his own furniture company. The two began working together and were married five years later. Their company would become “an international arbiter of style and design” featuring the furniture of—among others—Eero Saarinen, Bertoia, Mies van der Rohe, and Florence Knoll herself.

In 1946, Knoll became head of the Knoll Planning Unit, a service that was ahead of its time in offering clients a “total design” package. The approach of the Planning Unit was novel: researching and surveying clients to find out their needs and how they used a space, then using this information to create a complete, functional interior design. The Planning Unit made design history, although no one on the team realized it at the time. They were just “going along doing what [they] wanted to do” not knowing that their modern, efficient designs would shape “the ethos of the post-war business world” and open the door for high-profile projects with companies like IBM, CBS, and GM. (1stdibs, knoll.com)

The Planning Unit also designed the Knoll company’s showrooms as a way to highlight the modernist aesthetic. Florence Knoll’s design philosophy is especially apparent in these rooms. The San Francisco showroom created in 1954 and pictured below is one example:

Image from knoll.com.

Knoll often used floating colour blocks, screens, and foliage to delineate “rooms” where customers could sit and experience the furniture. It was a truly new approach. As designer Richard Schulz noted at the time, “You could walk into a Knoll showroom and see how the furniture worked.”

Knoll’s showrooms were spare yet balanced, conveying warmth and depth with simple touches of colour, texture, and natural elements. They perfectly captured the minimalist aesthetic the company was promoting. They also allowed the Knoll company to showcase the considerable talents of its designers. The San Francisco showroom, like many others, featured now iconic designs from Mies van der Rohe (the Barcelona chairs facing the coffee table in the foreground) and Eero Saarinen (the Womb chair, in blue at the back of the main floor). Also included? Designs from Florence Knoll herself--in this case, the white sofa and parallel bar settée near the Womb chair.

Although Knoll considered her pieces “filler,” intended to complete a space without drawing attention away from the work of other designers, today her designs have become as “revered and celebrated” as those of her colleagues. (Knoll Company: Florence Knoll, 1stdibs, Knoll Company: Knoll Showrooms)

As retailer 1stdibs notes, Florence Knoll’s designs were dedicated “to functionality and organization, and never flamboyant…pure functional design, exactingly built; their only ornament from the materials, such as wood and marble.”

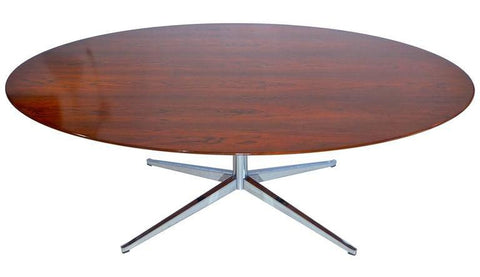

One of her most well known designs was a new take on the conference table. Recognizing the need for better sightlines, she used an oval shape instead of a traditional rectangle, as shown below. At 96 inches wide, this table offers ample space for meetings. It also demonstrates Knoll’s belief that materials provided sufficient ornamentation. The chrome base adds a strikingly modern element that beautifully complements the rosewood. Nothing else is needed:

Image from 1stdibs.

Knoll used a similar approach to her executive desk. Considering her criticism of the “heavy, ornate desks” that were common at the time, it is no surprise that her version is so streamlined. As with her conference table, the design is very clean and simple:

Image from 1stdibs.

In a 1964 entry about commercial interiors for the Encyclopedia Britannica, Knoll noted that behind most of the heavy, ornate desks in traditional offices there was typically a table that became “an unsightly storage receptacle.” (Knoll.com) Her solution? A sleek and highly functional credenza. This model, a very large 13 feet in length, was intended for use in an office and contains multiple filing and stationery drawers. The marble top adds subtle ornamentation:

Image from 1stdibs.

Like other designers of the period, Knoll often raised her furniture up on slim legs to provide a sense of lightness. Even her pedestal bases, seen above, had a feeling of airiness, given their sleek supports and elevation from the floor. Her use of high, narrow metal legs carried throughout much of her furniture, including storage and seating. One early example is this chest with a stainless steel frame:

Image from 1stdibs.

Her double-pedestal desk is another example:

Image from 1stdibs.

Knoll’s Parallel Bar series of sofas and armchairs, so named because of the bar at the back, includes the same style of leg:

Image from 1stdibs.

Her sofas have a similar base, including the long model with attached cabinet and three-piece sectional shown below:

Image from 1stdibs.

Image from 1stdibs.

Tables and benches had the same aesthetic, “a spare, geometric presence that reflects the rational design approach” Knoll learned from Mies van der Rohe. (Knoll.com) Her highly recognizable bench is shown below in a custom, 12-foot model:

Image from 1stdibs.

Although she maintained a consistent look throughout much of her furniture, Knoll—like all modernist designers—added visual interest through the materials she used. Granite, glass, and marble were among them:

Granite table on metal legs. Image from 1stdibs.

Glass-topped table. Image from 1stdibs.

Marble-topped coffee table. Image from 1stdibs.

Leather was another material Knoll used in her seating, seen in the black bench shown earlier and this custom-made cognac daybed:

Image from 1stdibs.

The leather and chrome combination continues in contemporary versions of her famous lounge chair design. This particular item is available new from the Knoll company:

Image from Knoll.com.

It is easy to imagine all of these pieces in an office lobby or the executive suite, and that was the genius of Florence Knoll’s designs. They were simple and easily adaptable to any interior. The clean, minimalist look of her furniture also makes it timeless—the pieces she created in the 1950s and 1960s fit seamlessly into today’s décor.

Florence worked at Knoll until her retirement in 1965, guiding the company throughout the period after Hans' death in 1955. Many of her designs are still being manufactured by the company, including the lounge chair shown above, and her executive desk, credenzas, bench, and tables.

Leave a comment