Great Mid-Century Designers 101: Charles and Ray Eames

Eames is an instantly recognizable name in the annals of mid-century design. The husband and wife team continually pushed the envelope as they sought to design practical, functional, and cost-effective furniture. They learned by doing and never shied away from trying new materials or investing the necessary time to find “the right answer” to design questions. They did not seek to create iconic designs, but in following their principle of “way-it-should-be-ness,” they did just that.

Charles & Ray Eames: Pushing Boundaries

Charles Eames was born in 1907 in St. Louis. From an early age, his gift for drawing was apparent, as was his thirst for knowledge and affinity for learning by doing. The latter skill would serve him well in his future as a designer.

His father died when he was just 15, meaning Charles had to take a job to support the family while going to school. He worked at the Laclede Steel Company in summer and on weekends during the school year, but still maintained excellent grades at school. After high school he received a scholarship to the architecture program at Washington University in St. Louis, not so much because of what he studied but because of his work at the steel mill. As part of his job he was asked to work with patterns and do some “vague engineering work.” As Eames himself said, “I would draw a lot and then I had been sort of introduced to the idea of architecture and because of this combination of experience and things, which was a little bit in advance of what would normally be expected, I was given a scholarship to the university.”

Eames never did graduate. He was asked to leave Washington University after four semesters because "[h]is views were too modern.” He asked his professors to broaden their view beyond Bauhaus and discuss Frank Lloyd Wright, who was seen as something of an outlier at the time. This “premature” interest in Frank Lloyd Wright did not sit well with the faculty and led to Eames' early departure from the university. (Eames Office: A Good Learner)

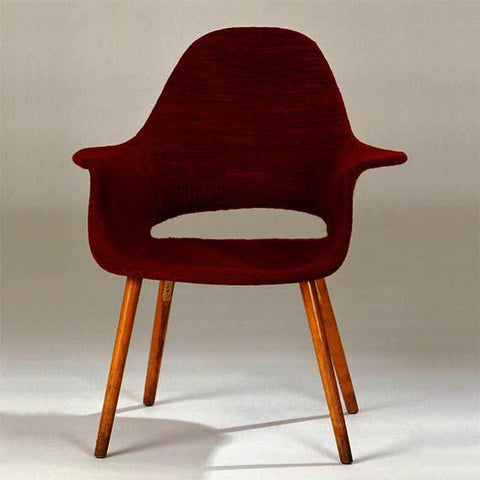

Ray Eames was born Beatrice Alexandra Kaiser in Sacramento in 1912. Little is known of her childhood, although it is said her artistic talent was recognized at a young age. When Ray was done high school, she and her widowed mother moved to New York where Ray studied art under abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. She met Charles in 1940 at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Detroit, the same place that Charles had met designer Eero Saarinen. Ray helped Charles and Saarinen prepare designs for the Museum of Modern Art’s 1940 Organic Furniture Competition. Eames and Saarinen won two first prizes, including one for their molded plywood “Organic Chair”:

Image from Vitra Design Museum

Charles and Ray married in 1941 and moved to California where their “extraordinary personal and artistic collaboration began.” Their goal was to “utilize new materials and technology, so that everyday objects of high quality in both form and function could be produced at reasonable cost.” (FemBio) To that end, they continued their experiments with molded plywood.

The Organic Chair had been a success from a design perspective, but the technology for mass production of furniture made of molded plywood with complex curves did not yet exist. Charles and Ray decided to figure out a solution. They developed something called the Kazam! Machine, shown below:

Image from the Eames Office.

The Eames Office describes how it worked:

“They started the process by placing a sheet of veneer into the Kazam! Machine mold and then they added a layer of glue on top of it. They repeated this process five to eleven times. Then, they used a bicycle pump to inflate a rubber balloon after the machine had been clamped shut, and the balloon pushed the wood against the form. Once the glue was set, Charles and Ray released the pressure and removed the seat from the mold, ‘ala Kazam!—like magic.’ (Hence the name). Finally, they used a handsaw to obtain the finished shape and hand-sanded the edges to make them smooth.”

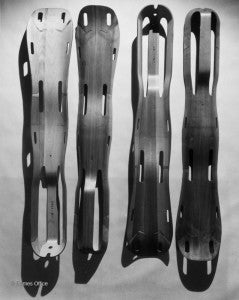

These experiments did not yield immediate results in the form of finished furniture, but they did provide a solution to another problem. In 1942, in the midst of World War II, the Eameses learned that the standard metal splints used by the military were causing further injury to soldiers, mainly because the metal stretcher bearers “amplified vibrations in the brace.” Charles and Ray created a molded plywood brace that conformed to the leg. The brace included symmetrical holes that relieved the stress of the bent plywood and provided a place for medical personnel to thread through bandages and wrappings. Because of their elegant design and historical significance, the braces are still considered collectible today.

Image from the Eames Office.

In addition to helping the Eameses gain a better understanding of a specific material—molded plywood—the invention of the leg splint led to a partnership with Evans Products which allowed the Eameses to increase production. Not only did they produce leg splints from molded plywood, but also airplane fuselages, arm splints, a body litter, and pilot seat. (The full story of the leg splint is here.)

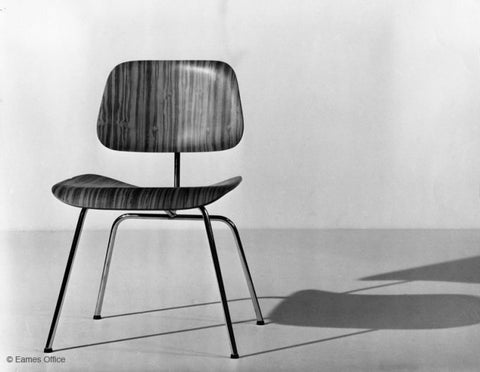

In 1946, with the war over, the Eames Office, as their production centre was now known, turned back to furniture. Five years after the invention of the Kazam! Machine, the Eameses would produce their first molded plywood chair, the LCW (Lounge Chair Wood):

Image from the Eames Office.

Time magazine called the LCW the “chair of the century.” It was evidence of the Eameses' belief in learning by doing. There were various iterations of the chair, including many attempts to create a single-piece shell. In the end, they settled with the curved legs and the two-part seat shown above. Did they regret spending five years developing one piece of furniture? No, said Charles to an inquiry about another piece. This work ensured that they had “the right answer.” (Eames Office: LCW)

After the LCW, the couple got the attention of manufacturer Herman Miller and entered into a production contract with the company. Herman Miller still produces their designs today. Other iconic pieces followed the LCW. Working with molded plywood and metal, the Eameses created the DCM (Dining Chair Metal):

Image from the Eames Office.

The DCM offered comfort rarely felt in wooden seating, namely because of its contours and the rubber mounts between the seat and legs that allowed the chair to flex and shift. (Eames Office: DCM)

Website 1stdibs notes that, although the Eameses “embraced new technology and materials,” one of their “peculiar talents was to imbue their supremely modern design with references to folk traditions.” As an example, they cite the Wire Chair from the early 1950s which was inspired by basket weaving techniques:

Image from the Eames Office.

Fibreglass was another new material the Eameses incorporated into their designs. The now famous fibreglass armchair, shown below, is an example of Charles and Ray’s belief in making things the way they should be made. As Charles said: “…when you set out to do a chair, you’re not setting out to do something that will floor somebody. You just want to do it the way it should be, so that it’s appropriate and reflects the way it’s made.” (Eames Office: Five Things About Charles and Ray Eames That Inspire Us Today) It was a design philosophy that echoed the Danish design ethos of the period: nothing extraneous and no excessive ornamentation, just excellent form and function.

Image from the Eames Office.

This armchair was originally created in stamped steel as part of the 1948 International Low-Cost Furniture Competition. (It won second prize.) Since steel proved to be problematic because of cost, coldness to the touch, and the potential for rust, Charles turned to fibreglass. (Eames Office: The History of the Eames Molded Plastic Chair.)The rest, as they say, is history. Charles and Ray would go on to produce other designs based on their fibreglass armchair, including “La Chaise” which was also entered in the low-cost furniture competition, and the very popular side or shell chair:

Image from the Eames Office.

Image from Eames Office. For a similar design, see the shell chairs now in-stock at VHB.

The couple continued working with molded plywood and in 1956 created yet another iconic design: the lounge chair and ottoman, also known as the 670/671. An original in rosewood is shown below:

Image from 1stdibs.

Comfort was the main goal of this design; Charles and Ray wanted it to have the “warm receptive look of a well-used first baseman’s mitt.” Still in production today, the 670/671 “remains a symbol of luxurious comfort.” (Eames Office: Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman)

The Eameses also worked with aluminum. Among the designs from their Aluminum Group was the EA 108 which was, and still is, a popular office chair owing to its sturdy, minimalist design:

Image from 1stdibs.

Beyond seating, the Eameses designed desks and storage units: lightweight, modular, and made of plywood, lacquered Masonite, and chrome-plated steel framing. Charles Eames noted that the units were as “simple and openly engineered as a bridge” and allowed for “exceptional economies in fabrication.” Like their other designs, the emphasis was on making things the best way possible with no excess or unnecessary complications. An original storage unit is shown below:

Image from 1stdibs.

Always experimenting and fulfilling their desire to learn new things, Charles and Ray worked in textiles, graphic design, and architecture. They created a series of exhibitions in partnership with IBM on everything from Copernicus to the Fibonacci sequence and computer technology. They also produced a number of films, including Powers of Ten which, as noted in its opening sequence, deals with “the relative size of things in the universe and the effect of adding another zero.” The significance of this groundbreaking short film was recognized when it was added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. (Slate magazine has an interesting overview of how the film was made, and the entire film is available for viewing on YouTube.)

Unsurprisingly, the couple also had a unique perspective on toys, believing that toys and games were not just for fun but were “preludes to serious ideas.” (Eames Office: House of Cards) They tried their hand at designing toys, including their very popular House of Cards, a set of slotted cards that could be used to create structures of various sizes and shapes. An original version is shown here:

Image from 1stdibs.

When asked by Alcoa to create a toy in aluminum, the Eameses experimented with different ideas and came up with something truly innovative. Having learned about photovoltaic cells while developing the toy, they decided to put them to use. The end result was the “Solar Do-Nothing Machine.” Video footage they took stayed hidden until their grandson discovered it and produced this short YouTube video:

In reality, the “do-nothing” machine did quite a bit. It was cited by Life magazine as a “forerunner of future solar-power machines” and, according to Mental Floss, the toy was a “relatively early use of solar power,” created at a time when 8% efficiency was considered cutting-edge.

Charles Eames passed away in 1978. Ray died exactly ten years later, to the day. Their designs are still in production today through Herman Miller and Vitra. The couple accomplished so much that it is hard to encompass it all here. For more insight into their prolific careers in design, visit www.eamesoffice.com.

Leave a comment