Great Mid-Century Designers 101: George Nelson

The name George Nelson is well known to fans of mid-century design. He is famously associated with furniture manufacturer Herman Miller, a company he “transformed” in his 27 years as design director, but Nelson’s legacy is wide ranging. Beyond furniture design, Nelson also made his mark as an author, editor, architect, industrial designer, graphic designer, teacher and “general provocateur.” (George Nelson Foundation)

George Nelson: Uncomplicated Design

George Nelson was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1908. He would later study architecture at Yale, an interest that came about quite by accident. According to Nelson himself, he ducked into the architecture school to wait out a rainstorm and became “entranced” by the student projects he saw. After graduate studies at Catholic University in Washington D.C. in the early 1930s, he competed for and won the Rome Prize, which enabled him to study at the American Academy in Rome.

While in Europe, Nelson conducted interviews with prominent architects, including Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius. Appearing as profiles in the American architectural journal Pencil Points, these interviews would launch Nelson’s writing career. By 1935, he was associate editor of both Architecture Forum and Fortune. He founded his own architectural practice soon after. He shut down the business during World War II, then moved onto teaching at Columbia University.

Nelson’s writing drew the attention of D.J. De Pree, president Herman Miller, who hired him as a designer in 1945. He would be appointed design director of the company in 1947. In that role, he would “forge the company’s image” and play “a key role in establishing Herman Miller as one of the most important modern American furniture producers.” (George Nelson Foundation.) Along the way, Nelson recruited “seminal” designers of the period, like Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, and Isamu Noguchi. (Design Within Reach) While working with Herman Miller, Nelson also established his own eponymous industrial design firm through which he began a collaboration with the Howard Miller Clock Company. (Howard was Herman’s brother.)

Despite all of this activity, he did not stop writing. His book Tomorrow’s House, written with the managing editor of Architectural Forum Henry Wright, showed why Nelson was considered a provocateur. The book was scathing in its criticism of contemporary home design, which he believed hewed to whatever trend was in fashion--English, French Provincial, Colonial--without regard for the needs of modern lives. He makes his viewpoint clear early in the first chapter:

“Today’s house is a peculiarly lifeless affair. The picture one sees in residential neighborhoods the country over is one of drab uniformity: pathetic little white boxes with dressed-up street fronts, each striving for individuality through meaningless changes in detail or color. The reason today’s house is so uninteresting is simply that it fails to echo life as we live it...Expressed in another way, it is hideously inefficient. Less honest thought goes into the design of the average middle-class house than into the fender of a cheap automobile.” ( Today’s House, Full text version.)

His writing in Tomorrow’s House shows that Nelson, like all mid-century modern designers, believed in efficiency and smart design where form follows function. To him it was all very simple: “[O]ne starts with a need, a problem, and ends up with a design for a thing. The basic rules are not complicated: a designed object has to do what it was made for.” (George Nelson Foundation)

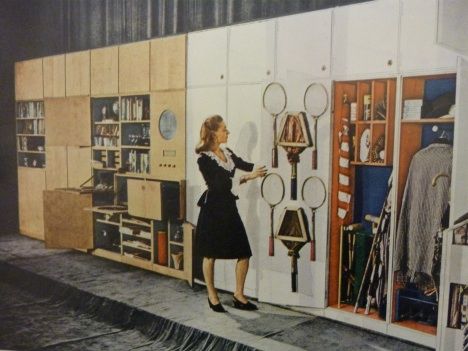

As will see, Nelson practiced what he preached, starting with a piece he developed for Tomorrow’s House: the Storagewall. Featured on the cover of Life magazine, the Storagewall epitomized Nelson’s philosophy on modern design. It was practical, modern, and made very efficient use of space:

Image from George Nelson Foundation, Storagewall.

The Storagewall was also the basis for Nelson’s work on storage systems, which he would turn to frequently during the next twenty years. One of his more renowned designs was launched in 1957. The Comprehensive Storage System (CSS) was a modular system designed for the home and later used in offices. It had many possible configurations and optional tables or desk units:

Another variation shows the table extensions and cabinets:

Images from George Nelson Foundation, CSS.

Nelson’s quest for efficiency extended to the workplace. The Herman Miller Research Corporation studied office environments, productivity, and people’s “enthusiasm at work.” The end result was Nelson’s Action Office series of furniture which presaged today’s trends toward desks of “differing heights...to encourage alternation between sitting and standing to promote concentration and creativity and thus increase efficiency.” Rolltop desks, like the one pictured below from VHB’s collection, allowed “unfinished work to simply remain on the desk in the evening, to be resumed the next morning without delay.” (George Nelson Foundation, Action Office)

Image from VHB collection.

Nelson has been credited as the inventor of the first L-shaped desk, with the furniture in his Executive Office Group (EOG). In his biography of Nelson, Stanley Abercrombie notes that L-shaped desks had been produced before by Herman Miller, so the EOG desk’s shape was not what made it unique. Rather, it was its “comprehensiveness.” With the EOG desk, Nelson had created the “first example of what came to be called a workstation.” It included two levels of work surface, multiple options for storage that fit above and below the desk, and even built-in lighting. Drawer units could also be installed on either side of the table. (Abercrombie, p. 207) One possible configuration is shown below:

Image from George Nelson Foundation, EOG.

Beyond his storage systems, Nelson designed other iconic pieces for the home. Among his most well known designs are those with the most interesting names: the Pretzel Chair, Coconut Chair, and Marshmallow Sofa.

True to its name, the Pretzel Chair has a rather twisted history. Originally known as the Laminated Chair and, later, as the 5890 and 5891, it first appeared in 1952 without armrests in a small series of twelve models. (Unlike later renditions, these originals also featured holes in the seat for attaching cushions.) High production costs bumped the chair’s price to $100, making it too expensive for Herman Miller to produce as a series. Five years later, a company called Lawrence Plycraft came up with a cheaper production method and made 100 of the chairs in walnut and birch. A dispute between the two companies put an end to production until 1985 when Nelson allowed the Italian firm ICF to produce the chair. A limited series of 1,000 was also created in 2008 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Nelson’s birth. (George Nelson Foundation, Pretzel Chair) Highly collectible, the original versions of this chair are extremely rare and can cost upwards of $6,000.00 each. (A clip from Antiques Roadshow proves the value.)

Image from 1stdibs.

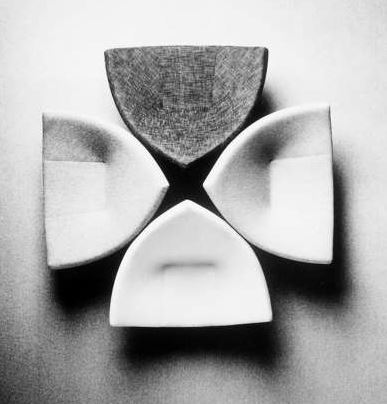

Like his contemporaries in the mid-century era, Nelson played with geometric shapes while also using technology to improve his designs. The Coconut Chair is one example. Nelson based it on the Winnipeg Chair created by Canada’s James Donahue (VHB Blog), refining the design to make it more of a triangle shape and adding bent steel rods to strengthen the base. His version was available in fabric or a very modern Naughahyde. It is still available from Herman Miller today, in the version shown below.

Image from Herman Miller.

A top-down view from a 1950s ad shows how the chair got its name, with the four chairs together resembling broken coconut shell.

Image from George Nelson Foundation, Coconut Chair.

Nelson and his associate Irving Harper fused geometry and technological innovation in the Marshmallow Sofa, shown below. An inventor who had developed an injection plastic disc approached Nelson and Harper, suggesting that the disc could be used as an inexpensive but durable cushion. Nelson and Harper were intrigued and put the discs on a metal frame. The original discs turned out to be more expensive and less practical than initially thought, but the unique look of the sofa appealed to both designers. Herman Miller ended up manufacturing the sofa, crediting its eye-catching appearance with ushering in the pop art style of the 1960s. (Herman Miller)

Image from George Nelson Foundation, Marshmallow Sofa.

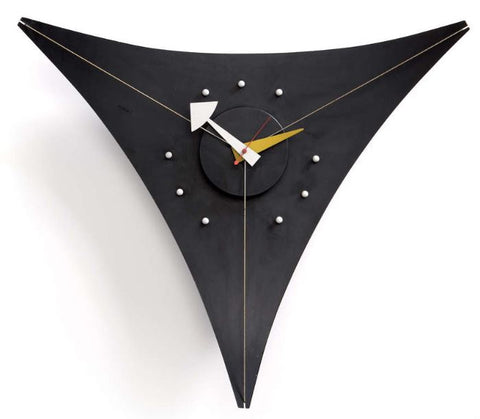

Geometry also featured in the clocks designed by Nelson’s firm for the Howard Miller Clock Company. Their most famous design was 1949’s Ball Clock:

Image from George Nelson Foundation, Triangle Clock.

Other accessories also got the Nelson treatment. With their famous bubble lamps, the designers at Nelson’s office stretched standard geometric shapes and experimented with new materials. Seeking to create a more modern version of silk-covered Swedish hanging lamps, Nelson’s team used a resinous lacquer developed by the military, sprayed it over a wire cage, then coated the whole thing in plastic to mimic the more expensive and finicky silk of the originals. The result was one of the firm’s most popular designs. The lamps are still sold today:

Image from George Nelson Foundation, Bubble Lamps.

The items featured here just scratch the surface. George Nelson was an extremely prolific designer who consistently put his beliefs into practice, exploring modern shapes, incorporating efficiency and practical functionality in aesthetically pleasing designs, and taking advantage of the technology available at the time. To read more about him and view his many designs, visit the George Nelson Foundation.

Leave a comment