Great Mid-Century Designers 101--Canadian Edition, Part One

With nationwide celebrations of our country’s 150th birthday taking place next month, we figured it’s the perfect time to shift the focus of our “Great Mid-Century Designers” series to Canada. In this short series of posts, we’ll look at the evolution of Canadian modern furniture and shine a spotlight on our most iconic mid-century designers.

With nationwide celebrations of our country’s 150th birthday taking place next month, we figured it’s the perfect time to shift the focus of our “Great Mid-Century Designers” series to Canada. In this short series of posts, we’ll look at the evolution of Canadian modern furniture and shine a spotlight on our most iconic mid-century designers.

To begin, we’ll provide a little historical context and talk about some of the first modern furniture designs produced in this country. These landmark pieces paved the way for the designers we will feature in our next post. (Read Part Two and Part Three.)

The Birth of Modern Design in Canada

By the time the second World War started, modern design was well established in Scandinavian countries and the US. In Canada, it was a different story. Although the country had a long history of excellence in woodworking and furniture manufacturing, it was slow to embrace modern design. Furniture manufacturers and retailers tended to be quite conservative, which worked against the widespread adoption of the modern aesthetic. Even if companies were interested in something fresh and new, they could license designs from American manufacturers and “benefit, at no cost, from the advertising of these products in the widely distributed American magazines.” (Wright, p. 111) As a result, few manufacturers were interested in investing in their own in-house designs. With no demand for homegrown designers, there was no impetus for Canadian schools to teach design or for people to pursue a career in the field, which led to further stagnation. (The job of “industrial designer,” a thriving profession elsewhere, did not even exist in Canada.)

A shift began during the war. Throughout the mid-1940s, discussion in magazines like Canadian Art and Canadian Homes and Gardens, among others, centred on the importance of developing the furniture industry. In a country with abundant natural resources, the furniture industry was seen as one that could “absorb a large part” the the country’s industrial production and output of raw materials. Some publications even criticized Canadian manufacturers for not applying technologies developed during the war to furniture production. E.W. Thrift, writing in Canadian Art in 1945, noted that the Canadian home furnishing industry was “a most backward field in its lack of the use of modern technology” and pushed for training programs for designers who could help modernize the industry.

Perhaps the sentiments of the era were best summarized by the reactions to an Art Gallery of Toronto exhibit called “Design in the Household.” Held in 1946, the exhibit included both Canadian products and pieces from New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Visitors to the exhibition left comments asking why “all the modern designs” were American. They also described the Canadian designs as small, plain, inferior, and impractical.

By 1949 the National Industrial Design Committee decided to take action. It published a brochure called “Good Design Will Sell Canadian Products” and distributed it to 6,000 companies. It also commissioned a study of the furniture industry that revealed an interest among manufacturers in creating new designs. This study recommended the expansion of design courses in Canada and more scholarships for Canadian students interested in studying design in the US. (Wright, pp. 88-130)

There is more to the story than outlined here, but the end result was increased opportunities for Canadian designers who took full advantage and made their mark. (For the full history, we recommend Virginia Wright’s Modern Furniture in Canada, 1920-1970)

Canada’s First Forays Into Mid-Century Modern Furniture

World War II forced restrictions on the supply of materials used in furniture making but also led to innovations that would later be used in the furniture industry. The Canadian Wooden Aircraft Company was one of the first to adapt wartime technology to furniture production. During the war the company made plywood components for Mosquito bombers. After the war, designers W. Waclaw Czerwinski and Hilary Stykolt used their expertise with bent laminated wood and moulded plywood to create a dining table and chairs with a modern aesthetic:

Image from MetroRetro Furniture.

The company created a lounge chair with a similar look:

Image from Archinect.com.

As Virginia White notes in Modern Furniture in Canada, 1920-1970, Czerwinski and Stykolt were greatly influenced by Finnish modern designer Alvar Aalto who had crafted this bentwood lounge chair in the early 1930s:

Image from MetMuseum.org.

In their creations, the two designers were heeding the advice of W.F. Holding, the chair of the Toronto Branch of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, who said in 1946 that products made in Canada did not need to be “instantly recognizable as being Canadian.” Rather, he thought that Canadian designers should take the “best from the past or from the inspiration of other countries.” (Wright, p. 92).

Holding was expressing a viewpoint very much in keeping with modern designers of the era who, as we noted in other posts in our Great Designers series, often re-interpreted designs from the past and from other cultures. (For examples, see our posts about Poul Hundevad, Kaare Klint, and Hans Wegner.)

Canadians may have also been a source of inspiration for others. In 1946, Canadian architects A.J. (James) Donahue and Douglas C. Simpson designed a prototype for the world’s first moulded-plastic chair:

Image from Furniture Link.

For their design, Donahue and Simpson incorporated materials used in WWII fighter planes, namely fibreglass and epoxy resins. The chair, which had no joints or attachments, was made of “ten layers of glass-fibre reinforced cotton, 3/16 of an inch in total thickness, moulded onto a reusable form with epoxy-resin adhesives, and baked in an autoclave at 350 degrees Celsius.” It was also fire- and acid-resistant. (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 78; Wright, p. 98)

Although never produced, this chair preceded by three years the now iconic shell chair by Charles and Ray Eames. It also came 16 years before a one-piece plastic school chair created by Italian designers Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper, seen here.

James Donahue had studied under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer at Harvard before returning to Canada to pursue a career as an educator and furniture designer. With his architecture students at the University of Manitoba, he developed yet another landmark piece that would serve as inspiration for a celebrated American designer.

Donahue’s Winnipeg chair, created in the late 1940s, included a bent plywood shell, rubber shock mounts, and a metal rod base. It is estimated that 200 of the chairs were produced and about two dozen of the highly collectible chairs exist now.

Image from Galerie Cazeault.

A version with a wood base was also made:

Image from 1stdibs.

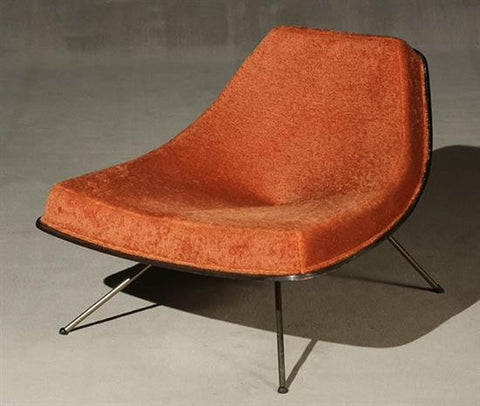

As for that famous American designer? It was George Nelson, who saw the Winnipeg Chair during a visit to a Canadian design expo.(1stdibs). Inspired by Donahue’s design, Nelson created his legendary Coconut chair for Herman Miller in 1955:

Image from 1stdibs.

In an interesting twist, Donahue’s Winnipeg Chair is now more commonly known as the Canadian Coconut chair, even though it was produced long before Nelson’s.

James Donahue was one of the founding members of the Affiliation of Canadian Industrial Designers, which, with its creation in 1946, helped establish the profession of industrial design in this country. Donahue, who died in 1997, has been remembered as “an influential teacher and architect with a passion for furniture design.” (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 237). In our next post, we’ll look at some of his contemporaries and their impact on Canadian modern design.

Sources:

Gotlieb, Rachel and Cora Golden. Design in Canada Since 1945: Fifty Years from Teakettles to Task Chairs. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2001.

Wright, Virginia. Modern Furniture in Canada, 1920-1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Post written by Crystal Smith.

thanks for the mention. You’ll be happy to hear there’s a lot more to the story. Have just completed a history of Canadian furniture manufacturing from 1860 to 1945. I’ll let you know when book is published – next year (I hope), cheers, virginia wright, Tasmania

Leave a comment