Great Mid-Century Designers 101--Canadian Edition, Part Two

Our series on great Canadian mid-century designers continues. (Read Part One here and Part Three here.) In this post, we will provide brief profiles of some of the more prominent Canadian designers of the era. Some were born here and some moved here from Europe, bringing their ideas about modern design with them.

Our series on great Canadian mid-century designers continues. (Read Part One here and Part Three here.) In this post, we will provide brief profiles of some of the more prominent Canadian designers of the era. Some were born here and some moved here from Europe, bringing their ideas about modern design with them.

Sigrun Bülow-Hübe

Sigrun Bülow-Hübe has been described as the person who “brought Scandinavian modern design to Canada.” (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 131) Born in Sweden, Bülow-Hübe studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts under Kaare Klint. She came to Canada in 1950 to work as a design consultant for the T. Eaton Company in Montréal. Her work there was far from satisfying. As she noted in a 1968 interview with Swedish magazine Möbelvärlden, she had hoped to spread “ideas of lightweight, practical, new furniture” in Canada but was not welcome to promote her own ideas, draw new furniture, or “propose anything that didn’t belong to the department store’s own traditions.” (Adams & Toromanoff, p. 12).

After three years at Eaton’s, Bülow-Hübe left the company and partnered with Reinhold Koller to establish AKA Works (later AKA Furniture). Finding Canadian furniture of the day too conservative, heavy, and large, she was now free to design pieces that aligned with her design aesthetic: timelessness with minimal decoration and an emphasis on comfort and utility. A 1964 article in Canadian Art contrasted her award-winning minimalist armchair with a typical Canadian design, showing the stark difference between her design goals and the prevailing trends in her adopted country:

Image from Hodges.

Bülow-Hübe’s armchair won a National Industrial Design Committee (NIDC) award in 1957. The adjustable backrest of the chair reflected her concern for comfort, and the design would later form the basis of a line of office furniture produced by AKA Furniture.

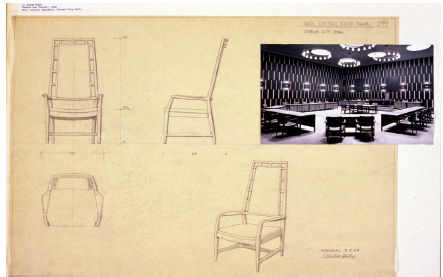

In 1958 Bülow-Hübe designed furnishings for Ottawa City Hall. Her sketches are shown below along with an inset of the finished chamber:

Image from Adams & Toromanoff.

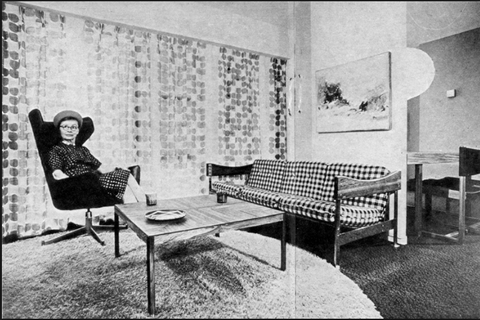

Bülow-Hübe would also be called upon to design a room for Moshe Safdie’s famous Habitat 67, as part of Expo 67. She was one of only two women among the twelve designers selected. As noted in the article “Kitchen Kinetics,” Bülow-Hübe did not choose pieces that would “complement the rather tough, modernist, concrete architecture.” Instead she opted for soft woods and printed textiles. The image below shows the designer in her suite, which featured drapes and a sofa she designed:

Image from Adams & Toromanoff.

Bülow-Hübe’s designs for AKA Furniture won twelve NIDC awards. After retiring from AKA in 1968, she worked as a researcher and, eventually, a senior design consultant with the National Design Council. In this role she aimed to “educate the Canadian public about the importance of design and attempt to bring out change at the national scale.” (Adams & Toromanoff).

Robin Bush

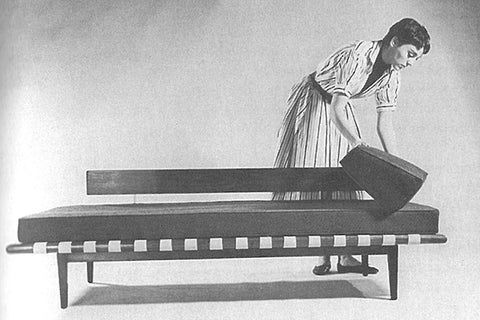

Born in Canada in 1921, Robin Bush studied at the Vancouver School of Art. He began his career as a designer when he partnered with Earle Morrison. The two designers made low-lying sofas and lounge chairs, like this sofa and Airform Lounge Chair:

Image from Wright.

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

In 1953, Bush set out on his own to form Robin Bush Associates Limited, through which he created his own furniture and sold Herman Miller products under license. Shortly after launching his company, he won a contract to supply metal frame furniture for Alcan’s mine at Kitimat. A 1959 article in Canadian Art emphasized Bush’s “intelligence and genius,” noting that Alcan chose Bush’s designs because they would increase comfort levels for workers and help retain employees. (Cited in Hodges.) The image below shows one of the sofas Bush created for the site:

Image from Kitimat Museum.

Bush’s early designs have been praised for their “clean, sharp and geometric” aesthetic and “interesting, and at the time, unusual colours.” (Hodges) After Kitimat, he continued working with metal and bold colours, creating the Prismasteel line for Canadian Office and School Furniture (COSF):

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

It was with COSF that Bush created his most memorable design. The Lollipop seating system featured comfortable curved backs in a unique circular shape. The system was completely modular, allowing for any number of seats to be added, along with circular side tables. In 1960 the Lollipop system was chosen for the new Toronto international airport terminal:

Image from Cool 60s Design Exhibit Review.

Bush left COSF in 1966 and began working in exhibition design before taking on the role of director at the Sheridan College School of Crafts and Design.

Peter Cotton

Also born in B.C., Peter Cotton studied architecture at the University of British Columbia intermittently in the 1940s while also serving in the war. He graduated in 1955 and helped establish the university’s School of Architecture. With his partner Alfred Staples, he opened Cotton Lamp Studio, which later became Perpetua Furniture. His designs were modest and economical, with wide appeal among the buying public and other architects.

Like his contemporary Robin Bush, Cotton also worked with metal. The spring-back dining chair is among his better known designs. It is made not of wrought iron, as it appears, but electrically welded steel rod, finished in black lacquer. (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 77).

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

Cotton was very concerned about “misuse of materials” and made his furniture as economically as possible. (CDR) The spring-back chair was easy to produce and weighed just 6.4 kg (14 pounds), making it affordable to ship. A high-backed version of the chair won an NIDC award in 1953. Wooden versions of the chair were also available:

Image from BC Museum.

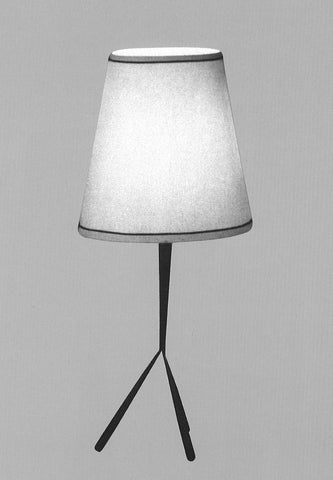

Economy was the reason for a change in Cotton’s lamp designs as well. One of his first lamps, shown below, was the tripod, which was hand-forged from steel. The follow-up design replaced the steel with bent rod and was known as the lug lamp. Cotton displayed the lamps with the cord wrapped around the leg, “artfully disguising the problem of a dangling cord.” (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 126)

Image from Gotlieb.

Image from The Consortium.

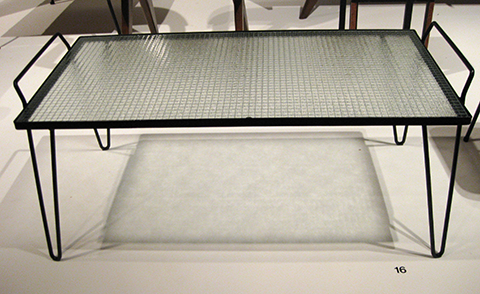

Cotton also produced coffee tables and armchairs with his bent rod technique:

Image from Sheila Zeller Interiors.

Image from Wright.

Perpetua Furniture closed in 1954. Peter Cotton went onto work with various historical and preservation societies.

Walter Nugent

A former student of Toronto’s Oakwood Collegiate, Walter Nugent was working as an advertising executive when he developed an interest in design. Virginia Wright claims he was inspired by a 1958 Art Gallery of Ontario exhibit that featured works by Florence Knoll and George Nelson, among others. Gotlieb and Golden reference a trip to Denmark as a possible influence. Either way, he was motivated to try his hand at design. Completely self-taught, he “shook up the Canadian furniture industry” with his design for a sprung steel chair. (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 247-248).

The revolutionary design “consisted of a one-piece seat-and-back frame made from a piece of bent, sprung steel rod” which was covered with a canvas sleeve, two cut sections of foam rubber that provided the chair’s cushioning, and, finally, a wool or vinyl sleeve.

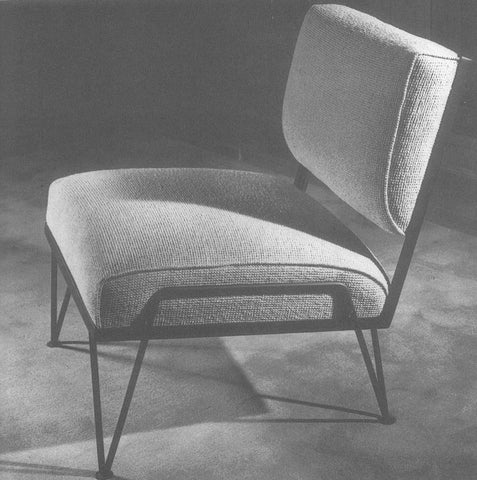

The striking design was also extremely versatile. Easily constructed and self-supporting, the seat could be attached to all kinds of different frames to make armchairs, multi-unit sofas, swivel desk chairs, or stacking chairs. (Wright) The two designs below show how very unique looks could be created from Nugent’s single seat design. The first, a walnut armchair from VHB’s collection, contrasts sharply with the metal and vinyl version that follows it, yet the seats share the same design:

Image from VHB.

Image from Gotlieb & Golden.

The vinyl and metal version was known as the #22 and was exhibited globally. Its various incarnations were produced for 15 years and won NIDC awards in 1960 and 1967.

Nugent’s pedestal coffee table was as versatile as his chairs. The standard chrome base, with either three or four legs, was made in various heights and topped with round, square, or oval tops made of glass or Arborite (Gotlieb & Golden):

Image from 1stdibs.

A close-up of the table's base shows the “spiralling arrangement of parts that animate the work.” (Canadian Design Resource)

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

Nugent had a dispute with investors and left his company in 1973 but Walter Nugent Designs continued making furniture until 1976.

Stefan Siwinski

Born in Poland in 1918, Stefan Siwinski relocated to Canada in 1952 and opened a small shop, sometimes called Korina Designs. He and his ten craftsmen made truly modern furniture out of a variety of materials, including plastic, metal, and wood. One of his first designs was this “playful” 3-legged dining chair that combined “Scandinavian organic modern with Pop imagery.” (Gotlieb & Golden, p. 91).

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

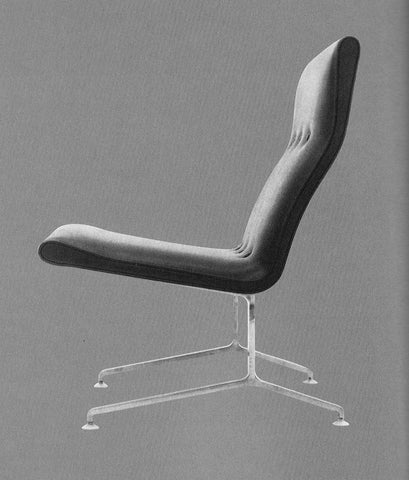

Like Robin Bush, Siwinski also had success designing furniture for commercial and public spaces, including airports. His lounge chair was used in many offices and, in 1960, was selected for the Toronto International airport departures lounge:

Image from Gotlieb & Golden.

In Design in Canada, Gotlieb and Golden make note of Siwinski’s “meticulous eye,” apparent in the lounge chair’s foam-rubber-and-vinyl upholstery which had to follow the shape of the seat without adding visible seams. To accomplish this design feat, Siwinski used heat and hand-stitching to mould the covers to the chair’s shell. Despite having only ten people in their shop, Siwinski and his team were able to produce 500 of these chairs in ten weeks to fulfill the airport order.

Siwinski also experimented with plastics, creating chairs from Plexiglass and fibreglass. He controlled all aspects of design and manufacture, from moulding to upholstery. Canadian Design Resource refers to the chair shown below as one of Canada’s most famous chairs and Siwinski as one of Canada’s “most creative furniture makers.”

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

The designer is shown, below, with another variation on his plastic tub chair.

Image from Canadian Design Resource.

Stefan Siwinski continued designing furniture into the 1980s.

In Part Three of this series, we’ll look at Jan Kuypers, Russell Spanner, and some of the major Canadian manufacturers of mid-century modern furniture. Read Part 3 Here.

Sources:

Adams, Annmarie and Don Toromanoff. “Kitchen Kinetics: Women’s Movements in Sigrun Bülow-Hübe’s Research.” Resources for Feminist Research/Documentation sur la recherche féministe. 34, nos. 3 & 4, 2015.

Gotlieb, Rachel and Cora Golden. Design in Canada Since 1945: Fifty Years from Teakettles to Task Chairs. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2001.

Hodges, Margareth. “Nationalism and Modernism: Rethinking Scandinavian Design in Canada, 1950-1970.” Revue d’art canadienne/Canadian Art Review. 40, no. 2, 2015.

Wright, Virginia. Modern Furniture in Canada, 1920-1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Post written by Crystal Smith.

Leave a comment